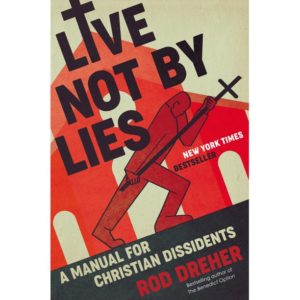

I just finished reading Rod Dreher’s new book, Live Not by Lies. It is not over-long; it’s a fast-paced read; and I highly recommend it. In the first half of the book, Dreher interviews many different people who lived through Soviet rule in Russia and Eastern Europe, and draws parallels with the kind of totalitarian instincts that seem to be on the rise in our culture today. The book is not alarmist, or filled with conspiracy theories. It is, rather, a sober, clear-eyed look at very public, well-known developments in main-stream culture, from the point of view of people who have a perspective that is very different from ours. The second half of the book uses insights from the interviews to detail some prescriptions for how Christians should think and live in a culture like ours, moving in the directions it’s moving. Dreher’s advice is practical and forward-thinking. It includes thoughts like these:

It is not over-long; it’s a fast-paced read; and I highly recommend it. In the first half of the book, Dreher interviews many different people who lived through Soviet rule in Russia and Eastern Europe, and draws parallels with the kind of totalitarian instincts that seem to be on the rise in our culture today. The book is not alarmist, or filled with conspiracy theories. It is, rather, a sober, clear-eyed look at very public, well-known developments in main-stream culture, from the point of view of people who have a perspective that is very different from ours. The second half of the book uses insights from the interviews to detail some prescriptions for how Christians should think and live in a culture like ours, moving in the directions it’s moving. Dreher’s advice is practical and forward-thinking. It includes thoughts like these:

- Value nothing more than truth. Refuse to repeat or support to lies.

- Families are resistance cells. Christians should be starting, cultivating, and guarding homes and families which are both protected from the culture, and open to all kinds of people who need help.

- Religion is the bedrock of resistance. Christians should cultivate a deep personal faith and obedience to Christ, as well as deep, real connections with other believers.

There’s a lot more, and it’s all helpful. Here’s an especially illuminating section to whet your appetite. Dreher writes about a Slovakian filmmaker named Timo Krizka, whose grandfather had been forced out of his ministry as a priest by the Soviets in the 1950s:

Several years ago, Krizka set out to honor his ancestor’s sacrifice by interviewing and photographing the still-living Slovak survivors of communists persecution, including original members or Father Kolakovic’s fellowship, the Family. As he made his rounds around his country, Krizka was shaken up not by the stories of suffering he heard – these he expected – but by the intense inner peace radiating from these elderly believers.

These men and women had been around Krizka’s age when they had everything taken from them but their faith in God. And yet, over and over, they told their young visitor that in prison they found inner liberation through suffering. One Christian, separated from his wife and five children and cast into solitary confinement, tested that he had moments then that were “like paradise.”

“It seemed that the less they were able to change the world around them, the stronger they had become,” Krizka tells me. “These people completely changed my understanding of freedom. My project changed from looking for victims to finding heroes. I stopped building a monument to the unjust past. I began too look for a message for us, the free people.”

The message he found was this: The secular liberal ideal of freedom so popular in the West, and among many in his post communist generation, is a lie. That is, the concept that real freedom is found by liberation the self from all binding commitments (to God, to marriage, to family), and by increasing worldly comforts – that is a road that leads to hell. Krizka observed that the only force in society standing in the middle of that wide road yelling “Stop!” were the traditional Christian Churches. And then it hit him.

“With our eyes fixed intently on the West, we could see how it was beginning to experience the same things we knew from the time of totalitarianism,” he tells me. “Once again, we are all being told that Christian values stand in the way of the people having a better life. History has already shown us how far this kind of thing can go. We also know what to do now, in terms of making life decisions.”

From his interviews with former Christian prisoners, Krizka also learned something important about himself. He has always thought that suffering was something to be escaped. Yet he never understood why the easier and freer his professional and personal life became, his happiness did not commensurately increase. His generation was the first one since the Second World War to know liberty – so why did he feel so anxious and never satisfied?

These meetings with elderly dissidents revealed a life-giving truth to the seeker. It was the same truth it took Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a tour through the hell of the Soviet gulag to learn.

“Accepting suffering is the beginning of our liberation,” he says.

“Suffering can be the source of the great strength. It gives us the power to resist. It is a gift from God that invites us to change. To start a revolution against the oppression. But for me, the oppressor was no longer the totalitarian communist regime. It’s not even the progressive liberal state. Meeting these hidden heroes started a revolution against the greatest totalitarian ruler of all: myself.”

Krizka discovered a subtle but immensely important truth: We ourselves are the ultimate rulers of our consciences. Hard totalitarianism depends on terrorizing us into surrendering our free consciences; soft totalitarianism uses fear as well, but mostly it bewitches us with therapeutic promises of entertainment, pleasure and comfort – including, in the phrase of Mustapha Mond, [Aldous] Huxley’s great dictator [in his novel Brave New World], “Christianity without tears.”

But truth cannot be separated from tears. To live in truth requires accepting suffering. In Brave New World, Mond appeals to John the Savage to leave his wild life in the woods and return to the comforts of civilization. The prophetic savage refuses the temptation.

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness, I want sin.”

“In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.”

This is the cost of liberty. This is what it means to live in truth. There is no other way. There is no escape from the struggle. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance – first of all, over our own hearts.

So there’s a taste of the book. Reading it wouldn’t be a bad use of some of the cold nights ahead in December.